Saturday, February 28, 2009

Internship with Movimiento contra la intolerancia

My position within the organization is two-fold. Half of my time is spent in local middle and high schools giving presentations and interactive seminars to students between the ages of 11 and 16 years. The other half is spent in the office, where I translate various materials, such as reports and informational materials that we send to other organizations, as well as published articles written by the President and other directors of the organization. Though I only started a month ago, I already have a sense of accomplishment, and I am fully enjoying being part of a team of highly-creative minds searching for a way to impact the future.

Comparing the Spanish and American etiquette in the work environment

The meeting.

The members of this meeting were creative thinkers and representatives of advertising firms. The objective of this meeting was to discuss innovative ideas for the next cultural event.

1. Almost everyone arrived late. According to the Spanish conduct of doing business, you cannot arrive more than 30 minutes late. Otherwise, it is considered rude.

American rule: You either arrive early or on time. No if ‘s, and’s, or but’s.

2. 1 person out of the whole meeting was carrying the conversation. It was almost a painful struggle to get other people to volunteer and share their ideas. Also, no one expressed any interest whatsoever. When I talked to my boss after the meeting, I asked him if he considered this meeting a success. He said, “Fue normal.” I was completely shocked. He explained to me that the Spanish people don’t like to work together and that there is almost no concept of teamwork in their business world.

Normally, during a meeting like this in America, people would be exchanging thoughts and be more open to different ideas and opportunities that other businesses would have to offer. I believe that American business thrives off of teamwork.

3. Texting and doodling. I understand having this habit in high school. But in a business meeting, this would be considered unprofessional and extremely rude. In the U.S., it would give you ticket/invitation straight to the door. Even though Elena and I did not call for this meeting, we were appalled and offended.

4. Pessimism. Sitting through that 3 hour meeting was almost unbearable. Crisis this and crisis that. Everyone understands and knows that we are all in an economic crisis. The point of this meeting was to simply discuss ideas for a cultural event. Instead, most of the people were thinking about their business’s financial situations even though nobody made a decision about a cultural event yet. La Fundación Málaga didn’t call this meeting to talk about financial support only.

Although all of this is all shocking and new to me, this is the Spanish way of conducting business. It’s only been a little over a month since I started this internship and I have yet to learn and experience more in the Spanish working environment.

Two Worlds and One Experience

The picaresque phenomenon: "Let's see if it works..."

Lazarillo de Tormes, the first true picaresque novel in Spain

This theme is particularly fascinating to me, because as Artal points out, la picaresca exists on every plane of Spanish society - from its children, the majority of which would rather claim unemployment benefit than have an actual job; to its politicians (although name a country which lacks corruption on a political level...). Although a portion of this conduct can be simply be chalked up to human behavior, the extent to which many Spaniards appear to carry out this trickery is worrisome to me. Maybe I'm overreacting, but I don't believe that raising kids to believe that it's all right to "get away with" everything they possibly can without applying effort is good for Spain's future.

Over at the Puerta del Sol blog, Jonathan Holland writes that la picaresca is "more often used in self-defence against bureaucratic excess" - which is understandable. Nevertheless, he then cites a study conducted by ABC in which 36.9% of university students claimed that copying in an exam is justified. I realize that coming from the United States, land of the rags-to-riches, everyone-can-succeed-with-hard-work myth makes me biased. Yet surveys such as these, for me, point to a defect in Spanish society that is only going to get worse if Spaniards do not become more "ashamed" than "proud" of this particular trait, to relate to Holland's observations. If the underhanded actions which characterize industries such as construction (to which Artal devotes much of her third chapter) continue, I hypothesize that the country will dig itself a bigger and bigger moral and economic hole that it may not be able to escape.

Friday, February 27, 2009

11

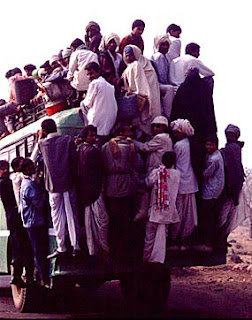

“El once”. Need I say more? For many of us in Malaga this bus is our life and blood when it comes to transportation. Our only means to get from El palo to El centro. For some it’s a time to reflect on their day or read a book. For the elderly of Malaga it’s their reunion room. After spending over an hour on this bus every day I have come to like the time I spend just sitting back and relaxing while watching the city go by. The bus can be overcrowded at times, just like every other one in the world. I often remember back to when I was in high school. I always took the number 8 bus down York road into Baltimore to go back home. I can’t help but making comparisons between these two famous bus lines in my life.

In the 11 I have become much more accustomed to the polite manner in which people uphold the “if you were there first, you get on the bus first” code of honor. Back home this was a very distant thought. The elderly were respected of course, but after that it’s everyone for them selves. The 11 also has good and thoughtful drivers. On more than one occasion I have seen them get out of their seat to help the elderly or the disabled. Switching to the 8 in Baltimore I have seen a driver skip a bus stop on the grounds that the wheel chair ramp doesn’t work and he didn’t want to deal with the man in the wheelchair waiting for the bus. As I said earlier the 11 can get packed, but I will always be left with the memories of the 8 when I was squished into the back corner of the bus with no way to get out and a man in a white suit sitting next to me preaching at the top of his lungs his version of the “word of Christ”. With these comparisons in mind I leave this entry with the hopes that I have many more culturally fulfilling rides on “el once”.

White Gold

Tourist Watching

Wednesday, February 25, 2009

The Invisible Malaga (Part 1)

Living in Malaga for the past six months, we were able to see some of the most beautiful things Spain has to offer as we have had the opportunity to travel to various parts across the country. I would like to talk not about these marvelous journeys however, but instead the far less attractive, but none the less interesting.

Living in Malaga for the past six months, we were able to see some of the most beautiful things Spain has to offer as we have had the opportunity to travel to various parts across the country. I would like to talk not about these marvelous journeys however, but instead the far less attractive, but none the less interesting.

It is true that you never know much about the place in which you are living unless you venture out and experience it on your own. It is quite clear that there is so much more to Malaga than El Palo,

Seeing these parts of Malaga made me think that every city/country has a side that it would like to remain hidden or invisible. However, I think that places like these tell us more about Malaga and opens up a sociological dialogue in terms of thinking about where we all from, the parts of society often ignored which in turn are very serious social problems that need to be addressed. The video below is from a program called Los Callejeros, which addresses different issues around Spain. La Palmilla was featured in a multiple part segment. Check it out!!! http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=zbOzpSpJqj0

Sunday, February 22, 2009

Cultural Comparisons and Our Subconscious Reactions

Wednesday, February 18, 2009

Language

We all have the similar fears and desires when it comes to language comprehension. “All I want to do is be able to speak and understand those speaking” which I myself have said and heard other mutter as well. We are able to use the Spanish we know now to understand class discussions and tours with Manolo, but what about on the street? How many times have you been in a position where someone asked a question and your response was to stare back at them and say; “Qué?” For some it’s an unnerving experience, while others will be able to salvage the situation and figure out what was said. The learning environment on the street is a much quicker and sometimes harrowing experience for those not accustomed to it. For those around us the game is different. Many of the thousands of students we see in the street all want to learn English. When we go to a restaurant and order, we constantly find that the waiter will reply in English. The Spaniards around us love to talk, but you get the feeling that they also love to talk at a certain “word per second” ratio. Also, the fact that Málaga is a tourist hub for many English speakers and for groups of students that stay for maximum one semester makes it all the more difficult for people to take us seriously in our desire to only speak Spanish. But for us the comprehension of Spanish will continue to be a road that we have to construct on our own. No one can build it for us.

Tuesday, February 10, 2009

Time Changes in Malaga

But as I arrived in Malaga i quickly learned that my time perception was quickly in the need of a readjustment. Due to the fact that classes here are at 4:14 pm most days i have the luxury to sleep in until 10:30-11 with all the time in the world. I usually do not have breakfast mostly because i am not usually hungry at 11 in the morning, so my usual "breakfast" consists of water. After taking my time in some daily reading or finishing up homework from the night before i usually find myself getting hungry at around 2:30 pm, wondering when lunch is going to be ready. Normally lunch is served at around 2:45 and it usually lasts about 20 minutes at the most followed by a few minutes of gathering my books and then making my way to the bus to go to class. As i said before classes begin at 4:15 and don’t end until 7pm. I usually end up taking the bus back to El Palo at around 7:30 and arriving at my house at the beautiful hour of 8.

Arriving home after an afternoon of classes, I am nether tired nor hungry but when 9:40 comes around i find myself once again wondering about food. Dinner usually lasts a good hour, mostly because my host family is very talkative and very curious about my day. The time to go out is also very different. Since at home, I find myself leaving my house at the latest 9:30 pm and stay out, at the latest, until 1:30 am. But here time is very different, by the time i finish dinner (usually at 10:30ish) I have time to get ready and go catch the 11 before it stops running for the night, and it changes into the N1. Calle Larios (the Center/Downtown part of Malaga) is usually close to empty at 11 at night, not because its late but rather because it´s early. Both the streets and the night-life locations do not fill up till about 1:30 in the morning. Due to the fact that people eat late and thus finishing their dinner at a much later time then 10, they find themselves leaving their houses to start their night of fun at about 12:30ish. People usually tend to stay out until the early hours of the morning, thus enjoying their free time and taking full advantage of the fact the work day does not really start until 9:30-10 the next morning.

Slowly i have changed my perception of time and have learned to adjust to the different timing of things here while also, from time to time, missing my old 'American' time. It will be very interesting to see if it will be another time shock to go back home at the end of the semester and try to readjust to my 'normal' routine. As for now, i am enjoying the abundance of 'free' time and the great opportunity of being in Spain and actually experiencing this difference first hand.

Monday, February 9, 2009

The kitchen

Simply put, there is never a shortage of food in the house. The pantry closets are overflowing, the refrigerator is so full sometimes the door cannot close, and the five-burner stove is hidden underneath the mess of pots and pans. On the counter sits the ornate pitcher filled with olive oil, which we refill every day from one of our four 5-liter jugs of olive oil in the pantry. As seasonal fruits come and go, our bottomless basket of fruit always displays an array of colors. From the typical apples and bananas to the exotic cherimoya and ever-present mandarins, fruit is a large portion of the culture of Spanish food. Another integral piece of the food puzzle in Malaga is the presence of seafood. Whether fried or in paella, the fruits of the sea are never missing from any meal. Lastly, we cannot forget the wine, which my host mother pours, in what seems like exorbitant amounts, over any dish before she pops it in the over, declaring that as a “good Catholic woman” she must baptize her food. All of these aspects, in addition to fresh ingredients and warm spirit of an eager cook, combine to make a unique kitchen atmosphere. Needless to say, in terms of the culture of food in Spain, their metaphoric cup runneth over.

In the richness of this culture of food, the problem that I face is that I cannot replicate the individual dishes or the sentiment they carry, when I return to the United States. My host mother does not own a single recipe and has never in her life used one. I fear that no matter how many hours I spent watching her bustle around the kitchen, I will never be able to recreate these Spanish dishes nor the passion and love she puts into them. I often stand in the kitchen watching her cook and listening as she rambles on about the neighbors or what happened in Mercadona this morning. Though I entered the kitchen with a book in hand, it takes only a few minutes before I realized that I would not be reading a word of it here. With a wooden spoon in hand stirring the rice, my host mother and I stood over the stove, deep in conversation, yet again.

Most importantly, I have learned that the kitchen is a place for conversation. As you can imagine, with the amount of food and the propensity of the Spanish to talk, the meals themselves last for hours; bring up religion and politics, and you’ve just guaranteed yourself at least another hour at the table. It is through this conversation that you will learn about the hearts and minds of those that surround you. When given this wonderful opportunity, sit and enjoy the conversation, and sometimes debate, that commences during the “sobre mesa.” However, if your schedule confines you to bocadillo on-the-go or a mere hour-long lunch, just stand in the kitchen for a while, quietly sipping your tea, and you will be amazed at what you can learn. Every dish has a story, whether it is the dish served for a Spanish ambassador or the time the oven caught fire, and there is a cook out there who would love to share this with you.

So go to the kitchen. Sit with your family, Spanish, American or otherwise, and talk. You never know what you can learn about a person or culture until you stay for a while in the heart of the home. As they say, “home is where the heart is,” and in Spain the heart resides in the kitchen.

- Marlena

Observations in a "guarderia"

So far, I have thoroughly enjoyed working in a guardería for my practica. It is a school for children between 0 and 3 years. As the guardería serves as one of the first institutions of learning for young children, next to their families, I believe that my internship will provide valuable insight into some of the basic values of the Spanish society.

Most of my time has been spent working with the 1 to 1 ½ year olds. As to be expected, some of the kids were unsure in the beginning what to think of me since I was someone new while others warmed up to me rather quickly. During certain parts of the day, all the children play together, allowing me to observe the different age groups. It has been quite interesting to see the development of the different ages and I hope to learn more ways to foster their learning. Also, if you think that understanding the Andaluz accent is tough, try understanding babies babbling in Spanish – quite difficult at times!

The Spanish children in the guardería are already beginning to learn English from an instructor who visits the school once a week to give hour lessons. I’m not there on the day that he comes, but the kids are fascinated to hear me speak in English such as when I sing English songs to them and love to demonstrate that they know simple words such as hello. This is one big difference that exists between

Another thing that I have noticed is that the Spanish are very insistent that the children learn to write with their right hand. Many times they color, and the teacher makes a big deal of showing them to color with their right hand while holding the paper down firmly with their left. If a child begins to color with the left hand, the teacher quickly corrects him or her and places the crayon back in the right hand.

~LindseyWednesday, February 4, 2009

Labor of Love

Intercultural observations - at school

As one can imagine, the Spanish classroom and its students are similar in many ways to their American counterparts – and very different in others. While I have learned about the educational system of Spain on paper, seeing the daily lives of students and teachers firsthand adds a whole new dimension to my perspective. Simultaneously, I am able to gain insight not only from the point of view of an American, teacher, and student of Spanish, but also from the perspective of a Spanish student trying to learn English. And after attending several classes and observing their struggles with the language, I have realized just how difficult English can be! As much as we complain sometimes about topics such as the subjunctive in Spanish, I think that English would drive me crazy with its countless prepositional phrases, among other details.

So far at Colegio El Limonar, I have taken note of how the classroom is run and how the students behave in general. On the first day I was surprised to hear the students calling their teacher by her first name, since I was expecting a more formal environment considering how everyone must wear a school uniform, the classroom are very plain, any tardiness is unacceptable, etc. Also, the customary method of teaching is lecturing and writing (usually extensive) notes on the board for the students to copy down. While we do this in the U.S. as well, it is more common for teachers to be more creative (at least in my experience, with foreign language classes). Subsequently, in a lecture-based class, the students are less engaged and seldom actively participate. So I can see how the “epidemic” of apathetic students in the U.S. is not confined to our borders; whenever the teacher poses a question in class here, it is rare to see a hand raised in response. Furthermore, I noticed in the ESO (secondary education) classes that a large percentage of students did not bother to complete their homework. I hope to make a difference in this matter by bringing an engaging activity into the classroom at least once a week, prompting the students to practice English and do something interesting for once.

According to our syllabus for this seminar, we should be able to reflect upon our internship experiences in a critical and informed way. However, in order to do so I can’t just sit here and create a list of how our two countries are different. Going at least one step further – asking “why?” after each observation – is essential if we are to attain any sort of “intercultural understanding” at all. For example, in Spain students need to choose at a much younger age what type of career they want to have, whereas in the U.S., even college students are still figuring out what their future entails. What does this say about Spanish society? For me, this observation points towards a higher degree of individualism in the U.S. than Spain, and also towards Spain's possible focus on ensuring a work force for the country. Furthermore, schooling is compulsory through age 16 in Spain, and free - demonstrating the importance of education here.

Monday, February 2, 2009

Introduction

Welcome to our experimental blog. Students who are living and studying in Malaga during the Spring, 2009 semester will be writing here about their experiences. We hope that these observations will contribute to our discussions of issues relating to culture and identity. Fourteen students will be contributing to this blog. Please feel free to comment!